They were wild 60s teens - until Liz's best friend became a nun.

Back then she pitied her. Now she wonders who had the best life.

My best friend Rosemary and I were hiding behind the bike sheds, drinking and smoking and discussing our hopes and plans for the future.

Dressed in the latest Sixties garb with towering beehives and thick black eyeliner, we may have been only teenagers, but we had it all worked out. Rosemary had decided on a career in the theatre, maybe producing or directing, and I was going to be a famous writer.

As we sat chatting so confidently, neither of us could possibly have known how dramatically our lives would diverge.

For while I went on to lead a rackety old life full of incident and adventure, at the age of 20, in 1964, Rosemary shocked everyone who knew her by taking the veil as a Carmelite nun, the strictest and most enclosed female monastic order of all.

Her decision — as mad as it seemed to me at the time — was not just a passing fancy, but a lifelong commitment and she has just marked 50 years as a nun.

As such, she invited me, her very oldest friend — whom she hadn’t seen for more than 40 years — to help her celebrate her silver jubilee at her monastery in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Now both in our 70s, I was intrigued to see the outcome of the diametrically opposed ways in which we had chosen to live our lives.

Rosemary Trolley and I met as babies in our prams and were pretty much inseparable from then on. My mother had known Rosemary’s mother since childhood. Their family lived in a flat above a tailor’s shop, opposite my mother’s flower shop on the High Street of St Neots in Cambridgeshire.

Rosemary and I wore the same clothes, sat next to each other in school, went on holiday together and were easily the most fashionable teenagers in our small, stifling home town.

We’d parade down the High Street, fancying ourselves in our tiny mini-skirts, make-up and high heels. The locals tut-tutted, especially when we started smoking as well, but what did we care? We would show ‘em!

Our families’ fortunes first diverged when Rosemary’s father Albert, a skilled cabinetmaker and carpenter, developed severe asthma, couldn’t work and had to go on the dole.

His family were mortified, and their reduced circumstances were highlighted by the fact my mother’s floristry business was starting to take off. We moved into a detached house in Avenue Road, where all the prosperous St Neots shopkeepers and businesspeople lived, and I inevitably saw a little less of Rosemary.

There was another setback when I went to the grammar school and Rosemary, in the cruel lottery that was the 11-plus, wasn’t offered a place. However, by her mid-teens things were back on track — both in Rosemary’s life and our friendship.

Her father was by now running the local Conservative Club, a job that came with spacious accommodation, and Rosemary had taken her O-levels at the Technical College and achieved the most brilliant results the town had ever known — far eclipsing mine.

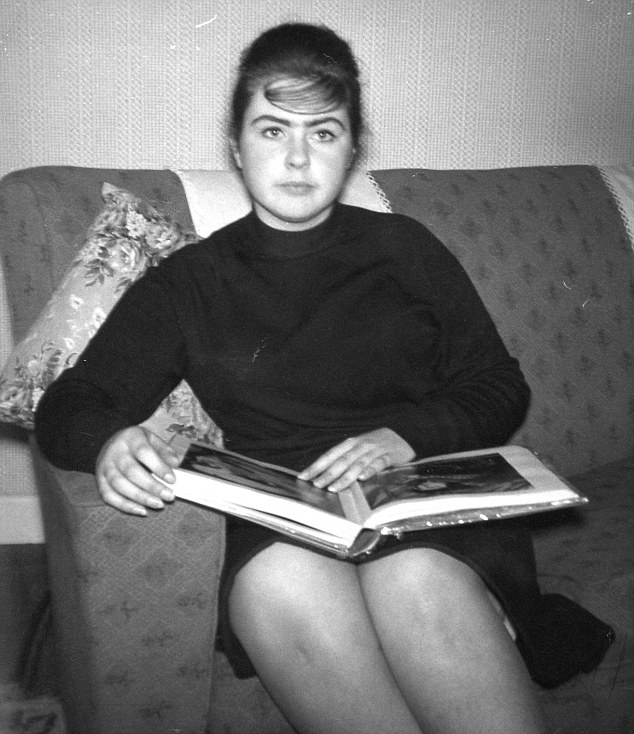

Bright young thing: A photo of Liz taken near Newcastle in 1966

Like me, she would go on to take A-levels, with the aim of going to university and escaping St Neots — something we couldn’t wait to do, or so I presumed.

How we were going to achieve our exotic dreams — Rosemary’s of the stage, mine of literary fame — we didn’t know, but at that moment anything was possible. Anything, that is, except settling down with a St Neots boy and getting married, a fate we viewed as worse than death.

We both had casual boyfriends, but were too ambitious to want to be trapped with a local boy.

‘You know Winifred King?’ asked Rosemary one day, mentioning a girl who lived nearby. ‘She’s getting married.’

‘But she’s only 16!’ I exclaimed. ‘St. Neots’ youngest bride!’

We shuddered. Never would such a fate befall us.

This, to us, was a horrible example of what happened if you let a boy from St Neots get too close. You were trapped for ever in a too-early marriage and stuck living next to your mum and dad for the rest of your life.

We, on the other hand, were carefree, with nothing more pressing to worry about than what to wear on our Saturday outings into town.

By the time she was 17, Rosemary looked like a young film star, highly groomed and poised, and certainly turned heads in St Neots.

Then, out of the blue, as we met one Saturday as usual, she asked: ‘Would you like to come with me to the Catholic Church?’

‘Why on earth would I do that?’

‘I’m getting interested in Catholicism,’ she said.

This was news to me. Rosemary came from a family who took little or no interest in religion, and she had stomped out of Sunday School at the age of ten, claiming she ‘didn’t need to be indoctrinated any more’.

We went in and, as Rosemary started genuflecting and making the sign of the Cross, I didn’t know what to think. Later, she told me she was taking instruction and converting to Catholicism. A few months later she said: ‘I’m giving up my A-levels. I’ve applied for a job teaching in a Catholic school.’

‘But what about university?’ I asked. ‘Your career?’

‘I’m giving all that up as well,’ she said. ‘I’m going to become a nun.’

A nun? My fashionable, fun-loving, ambitious, cigarette-smoking friend was going to become a nun, just as the Sixties were beginning to swing?

‘You’re not serious,’ I said. ‘You can’t be.’

Becoming a nun was the worst, the most bizarre lifestyle choice that I could imagine.

But she was serious, deadly serious.

From now on, instead of the fashionable clothes she loved, Rosemary — henceforth to be known as Sister Mary Clare of St Joseph — would wear a rough wool habit and home-made rope sandals.

Carmelites, a strictly contemplative order, believe that nothing must be allowed to interfere with their life of prayer and communion with God.

Hence every scrap of personal vanity has to be ruthlessly eradicated: there was not even a mirror in the tiny unheated cell of her convent in Waterbeach, Cambridge, where my friend would now sleep on a straw mattress.

She was not allowed to read newspapers or listen to the radio and would never again come out of the monastery, as Carmelite convents are known. Once she entered, age 20, she was keen for me to visit, and I remember going there in my Mary Quant dress, having to stub my fag out in the car park first.

By now, I was a liberated Sixties chick, having experienced several sexual relationships. I often reflected that Sister Mary Clare would be getting up just as I was rolling home from yet another drunken party.

What a contrast, and how odd when I entered a tiny little room, the only one where visitors were allowed. There was a wooden grille dividing the room down the middle, lined with ferocious-looking metal spikes.

Sister Mary Clare entered on the other side of the grille, wearing her habit, and told me about her new life. It sounded absolutely awful — five hours of prayer a day, spending most of the time in solitude and silence, with gardening and weeding for recreation.

We no longer had anything in common and I mourned the loss of my old friend as I left the monastery, thinking I’d never bother visiting again.

Back then: Rosemary Trolley (pictured) and Liz ‘met as babies in our prams and were pretty much inseparable from then on’

And I didn’t. I went on to enjoy an interesting and exciting career, got married, had children, had a good number of intimate relationships, travelled, moved house many times, and generally lived to the full the life of a modern woman, while Sister Mary Clare has spent her entire adult life praying and communing with God.

Heck, at 70 I’m still hanging in there, trying my best to remain slim, young-looking and fashionable, as vain and shallow as ever.

We had no contact at all for almost 50 years, until Sister Mary Clare’s brother told her he had seen an article I’d written in the Mail.

She wrote to me care of the paper, and we quickly struck up a regular correspondence. She told me that, when her English monastery had closed down in 1994, she made the decision, at the age of 50, to start a new life in Indiana, America.

As I stepped off the plane at Indianapolis airport, I wondered what would await me.

But even after all these years I recognised her immediately.

‘Mary Clare!’ I yelled, and we gave each other the most tremendous hug, tears and laughter mingling as we reconnected after nearly half a century apart.

I, of course, was wearing full make-up, whereas Mary Clare’s face had not seen cosmetics for 50 years. But her face was unlined and her eyes were twinkly beneath her glasses.

She certainly did not look 70. She looked happy, fulfilled and serene, and not at all burdened down by anxiety — unlike me, who lives with anxiety every day.

As much as I enjoyed our letters, when the invitation came to visit my old friend, my first instinct was to say no, especially as she lives an eight-hour flight away.

Yet I read and re-read her letter, mulled over her invitation, and eventually changed my mind. I would go to visit her.

So I prepared to meet somebody who was once my closest friend, but was now a virtual stranger.

What to talk about? No worries there. Once we started talking, we never stopped. Even after spending five hours a day in prayer and many hours in silence and solitude, it was obvious that Mary Clare had not lost her gift of the gab. I knew I would be staying at the nuns’ guest-house and, remembering the extreme austerity of the English monastery, was apprehensive about what it would be like.

Yet it was most luxuriously appointed, a little colonial-style bungalow separate from the actual monastery. Every day the nuns would bring over my meals, including wine, on a golf buggy, .

The monastery itself, closed to outsiders except on very special occasions, is entirely self-sufficient, and the 14 nuns who live there grow vegetables, keep bees and make greeting cards, icons and books, which they sell for income.

Mary Clare and I sat with her brother Philip, who had also flown over to visit with his wife Linda. We looked through Philip’s huge photo archive, screeching with laughter at pictures of ourselves as children at the time of the Coronation, and wearing swimsuits on holiday at Skegness.

We’d certainly had some fun together. But I wondered whether the setbacks Mary Clare had experienced as a teenager, with her family finances and failing her 11-plus, had influenced her decision to become a nun.

Stateside: Liz flew to Indianapolis, Indiana, where her old friend moved after her English monastery closed

‘It’s true that I wanted something permanent for myself,’ she said. ‘Something that could not be snatched away. It wasn’t just my growing desire to become a nun, though, that made me give up A-levels.

‘Dad’s health had started to go again and Mum needed help running the Conservative Club.

‘I couldn’t do both and we had to keep the job and the roof over our heads. Once I pulled out of A-levels, all thoughts of going to university were scuppered anyway.’

I wondered aloud if she regretted it now, missing out on university and never having a family of her own.

‘No,’ she said. ‘In the end, the calling to become a nun was unstoppable. I tried resisting it for ages, telling myself I wanted a career, possibly marriage and children. “Go away, Lord”, I kept saying.

‘But I started to feel a burning desire within me to devote my life to God, Jesus and prayer.

‘Once that happened, everything else simply faded away and I knew that if I said no, I would never be happy.

‘I have no misgivings, and nothing else, I am sure, could have brought me the peace and happiness that I have experienced in my life.

‘I knew that was what I wanted for myself, even though nobody else could understand it.’

I certainly couldn’t understand Mary Clare’s extreme decision at the time, but have since had some direct experience of the strength of that call, as my own husband Neville abandoned his home, his family and his career to follow an austere spiritual path, after joining the Brahma Kumaris, an Indian group run entirely by women.

The Brahma Kumaris espouse vegetarianism, celibacy and meditation, and more than 30 years later, he is as dedicated and devoted as ever.

All the nuns I spoke to agreed that devoting your life to God was like falling powerfully and passionately in love. ‘Except that this is permanent and God never lets you down,’ said Mary Clare.

She does not have a scintilla of regret that she never had a secular love affair or family of her own, saying: ‘I’ve been in love all my life.’

She has two nieces — Philip’s daughters — to whom she is close, and now great-nieces and nephews as well, and that is enough.

In comparison with her, I have had a lifetime of ups and downs, and far more than my fair share of men have let me down.

I’m still looking for love, and still not finding it.

While much of my life has turned to dust and ashes — my marriage ending, and the man I then fell in love with, John, dying, my career alternately collapsing and reviving, lovers leaving, coping with constant rejection and nothing being certain or guaranteed for very long — she is surrounded by a close and loving community. I, by contrast, am now entirely on my own.

If I observe the Great Silence — which the Carmelites do between the hours of 7.45pm and 8.45am the next morning — in my case it’s because I have nobody to talk to, and rather than being contemplative, it’s incredibly oppressive.

It’s ironic that at the age of just 20, my friend renounced everything, including her family and friends, yet I am the one who has ended up lonely, while her life continues to be busy and purposeful.

As I warmly hugged my oldest friend goodbye, I felt the irony of that fact wasn’t lost on either of us.

https://www.lizhodgkinson.com/images/uploads/general/article-0-1E9AF7B400000578-513_634x734.jpg